- Chapter 5: Meaning in Art

- Learning Outcomes

- Socio-Cultural Contexts – Historical Context

- Socio-Cultural Contexts – Social Context

- Socio-Cultural Context - Personal or Creative Narrative

- Socio-Cultural Context - Political Context

- Socio-Cultural Context - Scientific Context

- Horse Galloping

- Symbolism and Iconography

- Hindu Swastika

- Visual Literacy

- Seven Sacraments Altarpiece

- Symbolism and Iconography in Mythology and Storytelling

- Symbolic and Iconographic Motifs

- Winged Figures

- The Four Evangelists

- Metaphorical Meanings

- Presentation

- Lecture Video

- Quiz

Chapter 5: Meaning in Art

Socio-Cultural Contexts, Symbolism, and Iconography

Learning Outcomes

After completing this chapter, you should be able to:

- Assign works of art to historical, social, personal, political or scientific contexts.

- Explain and distinguish between symbolism and iconography.

- Indicate changes in symbols and iconographic motifs over time and in different cultures.

- Relate iconography to visual literacy.

- Describe connections between symbolism, iconography, and storytelling.

- Identify metaphorical meanings in art.

Socio-Cultural Contexts – Historical Context

- Historical context can help us interpret the content and understand the meaning of a work of art.

Art does not happen in a vacuum. Strong ties bind a work of art to the life of its creator, to the tradition it grows from and responds to, to the audience it was made for, and to the society in which it circulated. These circumstances form the context of art, the personal, social, cultural, and historical setting in which it was created, received, and interpreted. Historical context can help us interpret the content and understand the meaning of a work of art.

Video - Art historical analysis

Art historical analysis (painting), a basic introduction using Goya’s Third of May, 1808

Look for:

- formal properties

- subject matter

- historical context

Socio-Cultural Contexts – Social Context

- Social context can be helpful in determining elements of the life of the artist and how those elements impact the subject of the work and its underlying political, social and economic subtext.

This includes looking at the physical setting in which a work of art was to be experienced. Museums are the principal setting our society offers for encounters with art. Yet the vast majority of humankind’s artistic heritage was not created with museums in mind. It was not made to be set aside from life in a special place but, rather, to be part of life—both the lives of individuals and the lives of communities. Its meaning was united with its use. The piece shown here portrays a work of art as we might see it today in a museum. Isolated against a dark background and dramatically lit, the gilded carving gleams like a rare and precious object. We can admire the harmony of the sculpture’s gently rounded forms, yet the sculpture was not made primarily to be looked at in this way.

- Genre Painting: subjects or scenes of everyday life.

We also need to understand social norms and gender roles of a period and culture to understand Social Context. In the mid 19th century, the American industry and commerce was changing, and this had effects on the roles that women and men played in the home and in the labor force. We start to see women entering the work force in the mills and factories, and we start to see women demanding they have access to the world outside their domestic sphere. This included things such as politics, arts, and education. Women were still expected to maintain the domestic duty while men were the bread winners.

Video - Mending America, women and the Civil War

Mending America, women and the Civil War

Socio-Cultural Context - Personal or Creative Narrative

- Personal or creative narrative context combines the personal interpretation of the subject matter by the artist with a desire to share those experiences with the viewer.

- Georgia O’Keeffe portrayed her idea of beauty of the United States through the simplicity of the American Southwest and what she sees around her.

Personal or Creative Narrative allows us to get a glimpse of how an artists feels about a certain subject or location.

Video - O’Keeffe, The Lawrence Tree

Socio-Cultural Context - Political Context

During the often violent transition into our modern era, art was often deeply involved with politics. The perspective of the artist changed profoundly. Instead of exclusively serving those in power, the artist was now a citizen among other citizens and free to make art that took sides in the debates of the day.

Political works are often published or viewed years after they are created for fear of political repercussions, that they are perhaps too graphic or the wounds too painful for public release in the immediate decades after the war.

Socio-Cultural Context - Scientific Context

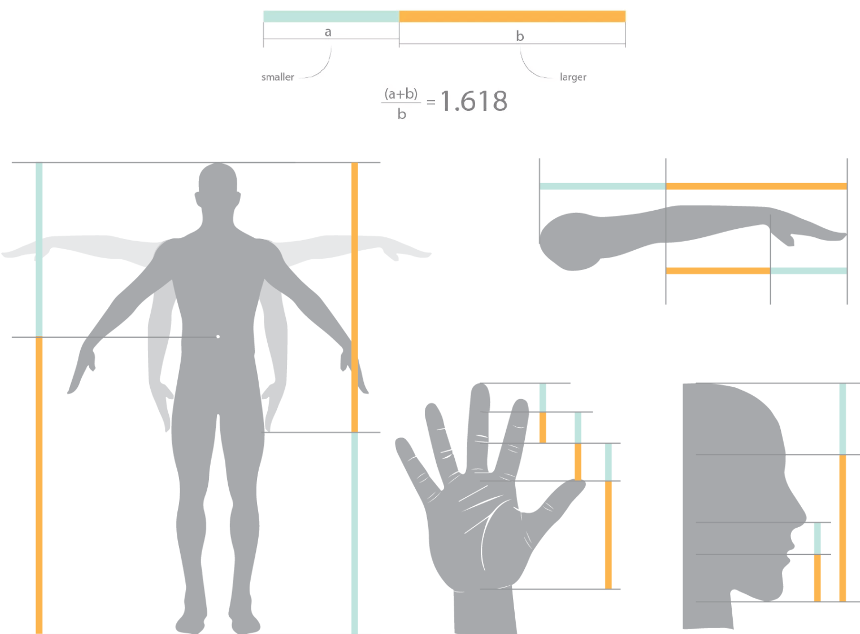

- Golden Ratio in the Human Body

- Golden Ratio – 1:1.618

Scientific Discoveries helped to advance art. Using the Fibonacci Sprial the Golden Ratio was discovered. Golden Ratio is seen in the Human Body. Results in the most visually pleasing proportions within and of an object or figure.

- Leonardo Da Vinci spent the last twelve years of his life systematically studying and documenting human anatomy.

Insights into function of the heart and growth of a fetus were accurate. Due to unrest in Milan he never published his works and they were lost. We have had to laboriously re-discover his findings by other artists and scientists, and in the work of Da Vinci that have been found around Europe.

Horse Galloping

Throughout history, artists have tried to create the illusion of motion in a still image. Painters have drawn galloping horses, running people, action of all kinds—never being sure that their depictions of the movement were “correct” and lifelike. To draw a running horse with absolute realism, for instance, the artist would have to freeze the horse in one moment of the run, but because the motion is too quick for the eye to follow, the artist had no assurance that a running horse ever does take a particular pose. In 1878, a man named Eadweard Muybridge addressed this problem, and the story behind his solution is a classic in the history of photography. Leland Stanford, a former governor of California, had bet a friend 25,000 dollars that a horse at full gallop sometimes has all four feet off the ground. Since observation by the naked eye could not settle the bet one way or the other, Stanford hired Muybridge, who was known as a photographer of landscapes, to photograph one of the governor’s racehorses. Muybridge devised an ingenious method to take the pictures. He set up twenty-four cameras, each connected to a black thread stretched across the racecourse. As Stanford’s mare ran down the track, she snapped the threads that triggered the cameras’ shutters—and proved conclusively that a running horse does gather all four feet off the ground at certain times. Stanford won the bet, and Muybridge went on to more ambitious studies of motion. In 1887, he published Animal Locomotion, his most important work. With 781 plates of people and animals in sequential motion, Animal Locomotion allowed the world to see for the first time what positions living creatures really assume when they move. Muybridge’s experiments in the 1880s had two direct descendants. One was stop-motion photography, which became possible as both films and cameras became faster and faster. The other was continuous-motion photography.

Symbolism and Iconography

- Symbolism: the use of specific figural or naturalistic images, or abstracted graphic signs that hold shared meaning within a group

- Iconography: the broader study and interpretation of subject matter and pictorial themes in a work of art

Iconography, literally “describing images,” involves identifying, describing, and interpreting subject matter in art. Iconography is an important activity of scholars who study art, and their work helps us to understand meanings that we might not be able to see for ourselves.

Hindu Swastika

While a symbol might have a common meaning for a certain group, it might be used with variations by or hold a different significance for other groups. The Swastika is a good example of this. An ancient sacred sign used in multiple cultures including India and the others throughout Asia and well as the Near East and Europe. A sign with implications of good future and positive movement. Adopted as the ground plan for Buddhist stupa worship centers.

The Emblem of the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei

- In the early 20th Century the Nazi Party appropriated the Hindu symbol of the swastika for use as a symbol of the superiority of the Aryan heritage

- Because of the events of the 1930s – 1940s

- The swastika now has a negative connotation

Visual Literacy

- “Visual literacy” should be considered a skill related to verbal and reading literacy for any didactic function.

Visual literacy or the ability to ‘read’ a work of art. Should be considered a skill related to verbal and reading literacy for any didactic function. By being able to ‘read’ a work of art we can understand the symbols and iconography better.

Seven Sacraments Altarpiece

- Triptych: a three-part or section format

Weyden created this work of art in a region and era that was know for having complex iconography. He was working in the Late Gothic and Northern Renaissance period. This work is called a triptych (or three part) altarpiece. The larger center piece draws the emphasis to the Crucifixion of Jesus. The smaller side panels show detailed descriptions of the 7 sacraments. A well instructed Christian would have been able to look beyond the central image and understand all the underlying meanings.

Symbolism and Iconography in Mythology and Storytelling

- Artist can enliven presentation of oral stories and myths with a figures posture, gesture, expression, and the use of symbolic props such as Herakles club and the tripod.

Deeds of heroes, tragic legends, folktales passed down through generations, episodes of television shows that everyone knows by heart—shared stories are one of the ways we create a sense of community. Artists have often turned to stories for subject matter, especially stories whose roots reach deep into their culture’s collective memory. We see artistic iconographic traditions that show strong relationships to beliefs and practices known from written sources. But at times that written documentation comes later. Art in Ancient Greece often showed stories of Greek mythology. Tales of warriors and gods are common. As are tales of great physical or intellectual contest like those of Herakles. Artist can enliven presentation of oral stories and myths with a figures posture, gesture, expression, and the use of symbolic props such as Herakles club and the tripod.

Symbolic and Iconographic Motifs

- Symbolic motifs can carry a different meaning in one context from what they might in another.

- Symbols are not universal.

When we look at symbols and iconography we can begin to see motifs, or dominate designs or symbols. A symbolic motif can carry a different meaning depending on when and when a work was created. Symbols are not universal. Things like flowers or candles can carry many different meanings.

Winged Figures

Winged figures have appeared in art in many cultures. They generally represent beings that can travel between terrestrial and celestial realms. Their more specific roles can vary widely, for good or evil purposes. In Ancient Greece and Rome winged creatures were known as Nikes (Goddess of Victory). The Egyptian Goddess Isis another example of a winged figure.

The Four Evangelists

- Halo – circular area of light appearing behind the head of a person or creature.

- Aureole (Mandorla) – a pointed circle of light or radiance surrounding a holy figure.

In Christian iconography there are winged figures that represent the Four Evangelists: Matthew is the winged man or angel. Mark, the winged lion. Luke, a winged ox. John, a winged eagle.

Metaphorical Meanings

- Metaphor – a figure of speech in which one thing symbolically stands in for another, perhaps unrelated, thing or idea.

Metaphorical meanings depend upon a certain level of view knowledge and insight.